I wrote this introduction for The Romantic Spirit in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien (2024) which I co-edited with Dr. Julian Eilmann. It is reproduced with the kind permission of Walking Tree Publishers. The full book in which this introduction features is available here. A recording of me reading the introduction is available on my YouTube channel here.

p.xv

In the conclusive scene of Peter Jackson’s adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The

Fellowship of the Ring (2001), Frodo and Sam reach a precipice and survey

the lands between themselves and Mordor. The camera rises behind them,

framing the landscape with the hobbits in the foreground, their backs to the

audience. Supported by Howard Shore’s lyrical, emotionally rich rendition of

the leitmotif ‘A Hobbit’s Understanding’, the camera settles onto a shot that

tips its cap to Casper David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above The Sea Of Fog (1818), a painting renowned for representing a particular aesthetic and philosophy that came to be known as Romanticism during the nineteenth century. Although this is an adaptation, Tolkien’s original work frequently embodies the Romantic employment of the Rückenfigur (‘back-figure’) by artists such as Friedrich, novelists like Sir Walter Scott, and poets such as Lord Byron. Consider, for example, how Tolkien frames the reveal of Caras Galadhon, Tuor’s coming to the sea, or the first glimpse of the Lonely Mountain; all of these acknowledge the importance of the Romantic Rückenfigur, the lyrical ‘I’ that represented the artist’s/author’s renderings and impressions of the world’s sublimity or beauty. All of these are quintessential examples of Romanticism’s subject-object symbiosis

and evinces how Tolkien’s legendarium is permeated by a Romantic spirit akin to Friedrich’s painting. Whether a conscious or unconscious act, Tolkien was incorporating and building on tropes, ideals, worldviews and aesthetics that were, during his lifetime, associated with Romantic artists, philosophers and authors. However, as the last sentence indicates, one shoe does not fit all. The following introduction will elucidate what this means and its implications for Tolkien studies, paving the way for fresh perspectives on Tolkien’s relationship with Romanticism as an aesthetic, literary, and philosophical phenomenon.

The labels ‘Romanticism’ and ‘Romantic’ are riddled with historical complexities and their ever-evolving nature underpins their complex relationship with Classicism and the Enlightenment. As Jerrold E. Hogle summarises, p.xvi Romanticism “has become problematic as a way of describing a cacophonous totality of conflicting voices, ideologies, gender roles, classes, genres, styles, and modes of publication” (2010: 2). The diverse range of voices and approaches has brought the labels under scrutiny, problematising attempts to capture the meaning of Romanticism in a simple list.

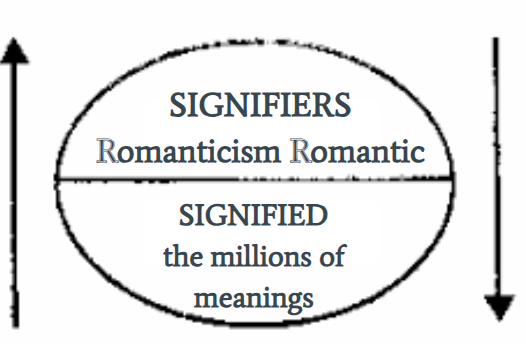

If we employ Ferdinand de Saussure’s theory of semiotics, we can see that the concepts of Romanticism and the Romantic (signifiers) have multiplied in

meaning and form (signified), moving from a systematised,

structuralist coding that seeks to “understand concepts through their relation to other concepts” (Parker 2008: 40), to a deconstructive understanding of the signifier’s potential for “multiplicity” (77). From their etymological origins with the Old French romanz and its affiliation with Medieval quest-romance, through their association with the Gothic Revival in the eighteenth century and connection with the Romantics in the nineteenth century, Romanticism and the Romantic continuously mutated, growing until their very meanings collapsed in on themselves in the twentieth century, becoming “vague and diffuse” (Casaliggi and Fermanis 2016: 3).

The nineteenth century saw the paradoxical expansion of Romantic aesthetics and its partial rejection with the rise of Victorian realism. Although the latter sought to distance itself from Romanticism, distillations of Romantic aesthetics and ideals developed significantly during the nineteenth century. The “reevaluation of Romantic aesthetic theory in the period 1870-1920 is evident in the values of the Decadent, or ‘art for art’s sake’ movement” as well as in groups such as the Pre-Raphaelites to which William Morris, a significant influence for Tolkien, belonged (Casaliggi and Fermanis 2016: 201-2). Although Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites have frequently been connected to Tolkien, it is only recently that they have been posited as links in the chain of influence from the Romantics.1 This situates Tolkien as an inheritor of Romantic aesthetics and p.xvii ideals through the nineteenth century’s reworkings of Romanticism, continuing its legacy into the twentieth century in the form of his legendarium.

After its evolution in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, the rise of Romanticist criticism, and Romanticism’s self-canonisation towards the end of the nineteenth century (Whalley 1972: 157), Arthur O. Lovejoy declared in 1924 that “the word ‘romantic’ has come to mean so many things that, by itself, it means nothing” (232). This notion was echoed by Tolkien’s colleague, close friend, and fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis, in 1943: “Romantic is a word of such varying sense that it has become useless and should be banished from our vocabulary” (2018: ix).2 Lovejoy remedied Romanticism’s ‘death’ by theorising a “plurality” of Romanticisms as Romantic authors were either logically independent or worked in close-knit groups like the Lake Poets, Cockney Poets and the Shelley-Byron Circle (1924: 236). René Wellek, however, explicitly countered Lovejoy by returning to the singular vision that the “major romantic movements form a unity of theories, philosophies, and style[s]” which “form a coherent group of ideas each of which implicates the other” (1949: 193). He concentrated Romanticism down to “imagination for the view of poetry, nature for the view of the world, and symbol and myth for poetic style” (1949: 201). With the rise of post-structuralism, Wellek’s structuralist mapping of Romantic ideas “collapsed”, giving way to more “vigorous” investigations into individual authors and the “civil wars of the Romantic movement itself” (McGann 2002: 236-7). William Wordsworth was the “model Romantic lyrist for twentieth-century academics”, but Jerome McGann has since challenged his centrality through his scholarship on Byron, and his 1993 The New Oxford Book of Romantic Period Verse reoriented author canonicity by organising poems by date rather than author (2002: 95).

The 1970s and 1980s gave birth to New Historicism, a revival of how Old

Historicism “read history and literature together, with each influencing the other” (Parker 2008: 219) but with the intention of distancing itself from previous “scholarship and criticism of Romanticism and its works [that we]re dominated p.xviii by a Romantic Ideology, by an uncritical absorption in Romanticism’s own self-representations” (McGann 1983: 1). These Marxist readings questioned the traditional markers and ideologies of Romanticism, situating Romantic texts definitively within their context. This resulted in a further splintering of Romanticism and the Romantic, challenging scholars to look beyond the former as a single chronological period, preferring a polychronic approach foundered on geographical regions and individual authors. For instance, English Romanticism has historically been considered to have ‘started’ in 1789 with the rise of the French Revolution. However, this eclipses how pivotal the American War of Independence (1775-1783) was, the resulting popularity of humanitarianism, and, as Aidan Day has shown, Romanticism’s philosophical and aesthetic roots in the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century (2001: 7-78).

1789 also fails to correspond with wider European and transatlantic Romanticisms as regional and national studies have questioned Romantic periodicity. Scholars have debated whether Scottish Romanticism rose with the ‘vernacular revival’ of the Scots-language in the 1720s, James Macpherson’s Ossian forgeries in the 1760s, or Robert Burns’s early poetry in the 1780s. Additionally, Germany’s Sturm und Drang movement of the 1770s signalled a new aesthetic direction for the German Enlightenment. Although they are not considered Romantics in Germany, authors such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller started to experiment with aesthetics and sensibilities that would later become central to German Romanticism.

The Romantic as a unified transhistorical aesthetic was also heavily criticised

in New Historicist studies, which sought to delineate authors’ personal aesthetics and understand how aspects such as “conflicting voices, ideologies, gender roles, classes, genres, styles, and modes of publication” impacted an author’s individual Romanticism (Hogle 2010: 2).3

Given this extremely brief overview of Romanticist scholarship’s evolution in the twentieth century, it should now make sense why it would be outdated for a Tolkien scholar to discuss Romanticism or the Romantic as unified signi-

p.xix fiers with clear, outlined parameters and meanings. If Tolkien scholarship were to continue to perpetuate this view, as many have, the field would fail to progress as it would be relying on outdated models of Romanticist research to read Tolkien’s own Romanticism. There are two ways to remedy this: 1) by acknowledging the growth of Romanticist scholarship during Tolkien’s lifetime and consciously situating his work in relation to these theories, therefore elucidating the conversations taking place around Tolkien; 2) drawing on recent developments in Romantic criticism to enrich our readings of Tolkien, therefore keeping current scholarship relevant and up to date.

Historically, Romanticism has been woefully overlooked in Tolkien scholarship. Although there are studies that exist as far back as the 1960s, they are sparse and Tolkien’s dialogue with Samuel Taylor Coleridge in ‘On Fairy-stories’ dominates the field. It has also been common practice for Tolkien scholars to refer to Romanticism or the Romantic without explicitly explaining what they mean by the terms. John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War (2003) liberally uses them without ever clarifying what he means or how they are Romantic. In a similar vein, some of the key scholarly texts on Tolkien like Tom Shippey’s The Road to Middle-earth (1982) and Tolkien: Author of the Century (2000), Brian Rosebury’s Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon (2003), and Wayne Hammond’s and Christina Scull’s third edition of J.R.R. Tolkien Chronology and Guide (2017) do not provide any explanation of what they mean by ‘Romantic’ or ‘Romanticism’. Their dominance in the Tolkien field sets a low standard for future scholarly engagement with Romanticist scholarship, internalising the Romantic Ideology that McGann warned against and misleading subsequent scholars. Furthermore, they overshadow scholarship that works with specific components of Romanticism and the Romantic. Patrick Curry’s Defending Middle-earth (1997) posits The Lord of the Rings directly in the Romantic ecological tradition examined by Jonathan Bate in Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition (1991). David Sandner’s ‘The Fantastic Sublime: Tolkien’s “On Fairy-Stories” and the Romantic Sublime’ (1997) and John Hunter’s ‘The Reanimation of Antiquity and the Resistance to History: Macpherson-Scott-Tolkien’ (2005) discuss Tolkien’s reshaping of distinct Romantic discourses. Dimitra Fimi’s Tolkien, Race and Cultural

History (2009) explicitly examines the influence of Romantic nationalism on The Book of Lost Tales. Michael Milburn’s ‘Coleridge’s Definition of Imagination and p.xx Tolkien’s Definition(s) of Faery’ (2010) is thus far the most convincing examination of Tolkien’s tussles with Coleridge’s ‘suspension of disbelief.’ Additionally, Julian Eilmann’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Romanticist and Poet (2017) discusses Tolkien’s work in dialogue with the German Romantic literature and philosophy that he was exposed to through the works of Edith Nesbit, George MacDonald, and Lord Dunsany, widening the perspective of Tolkien’s Romanticism which has previously been situated within the British Romantic tradition. More of the latter scholarship is required to counteract the former and steer the Romantic Tolkien discussion away from, to recall Casaliggi and Fermanis, the vagueness and diffuseness of Romanticism and the Romantic. By embracing their rich diversity, Tolkien studies will gain a clearer picture of how Tolkien is Romantic.

The Romantic Spirit in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien is a step in this new direction. It offers fresh perspectives on Tolkien’s relationship with English, Scottish, German, transatlantic, musical and artistic Romanticisms, working in concert to open up our discussions of Tolkien’s Romantic Spirit(s). The volume has been structured according to specific Romantic components that exemplify Romanticism’s extensive appeal for Tolkien scholars: Nationalism, History, and the Other; Language, Art, and Music; Imagination, Desire, and Sensation; and Nature and Travel. Taken individually, these terms have been analysed solely in relation to Tolkien’s writings and views. However, as was noted above, only a few have been applied under the Romantic Tolkien lens and the list is by no means exhausted by the current volume. The Romantic Spirit in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien celebrates the multiplicity of Romanticism and intends to ignite further discussion on Tolkien’s Romanticism, leaving behind Romanticism’s and the Romantic’s vagueness and diffuseness for its ever-growing cast of voices.

Bibliography

Casaliggi, Carmen and Porscha Fermanis. 2016. Romanticism: A Literary and

Cultural History. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

Day, Aidan. 2001. Romanticism: The New Critical Idiom. London and New York: Routledge.

Hogle, Jerrold E. 2010. ‘Romanticism: “schools” of criticism and theory.’ In Stuart Curran (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1-33.

Lewis, C.S. 2018. The Pilgrim’s Regress. London: William Collins.

Lovejoy, Arthur O. 1924. ‘On the Discrimination of Romanticism.’ PMLA 39.2:

229-253.

McGann, Jerome. 1983. The Romantic Ideology: A Critical Investigation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

— 2002. Byron and Romanticism. Ed. James Soderholm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parker, Robert Dale. 2008. How to Interpret Literature: Critical Theory for Literary and Cultural Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wellek, René. 1949. ‘The Concept of “Romanticism” in Literary History.’ In

Robert F. Gleckner and Gerald E. Enscoe (ed.). 1962. Romanticism: Points of

View. Princeton: Princeton-Hall Inc, 192-211.

Whalley, George. 1972. ‘England: Romantic – Romanticism.’ In Hans Eichner

(ed.). “Romantic” and its Cognates: The European History of a Word. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 157-262.

Endnotes

- See Marie-Noëlle Biemer’s ‘Disenchanted with their Age: Keats’s, Morris’s, and Tolkien’s Great Escape’ Hither Shore 07 (2010), Will Sherwood’s The ‘Romantic Faëry’: Keats, Tolkien, and the Perilous Realm https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/40585/SherwoodW.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (pages 12, 38, 141) (2020), and Annise Rogers’ ‘Overlooked Artistic Avenues: How William Blake’s art indirectly influenced the art of J.R.R. Tolkien’ in the current

volume. ↩︎ - Ironically, Lewis goes on to define the seven kinds of Romanticism, tying each to specific authors and Romanticists: 1) stories about dangerous adventures, 2) the marvellous, 3) art dealing with ‘Titanic’ characters, 4) indulgence in the abnormal, 5) egoism and subjectivism, 6) revolt against existing civilisation and conventions, 7) sensibility to natural objects (2018: x). ↩︎

- See New Historicist work such as Jerome McGann’s The Romantic Ideology: A Critical Investigation (1983), ‘Rethinking Romanticism’ (2002: 236-55), and Clifford Siskin’s The Historicity of Romantic Discourse (1988). ↩︎

Leave a comment