In my last blog post I explored the mother tree concept in Middle-earth’s woods and forests. In this one I want to pivot from the science of Arda towards its music. In writing my most recent PhD chapter I came across a book by Bernie Krause called The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (2012) and was struck by what I read. It led me down yet another tangential path, this time into music theory. In this blog post I want to lightly highlight, examine, and speculate on what soundscape ecology can do for anyone reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s works – whether set in or about Middle-earth or not! My hope is that you will pore over your next Tolkien book and think more deeply about how Tolkien presents the sounds of Middle-earth.

Terminology

Soundscape ecology: an academic discipline devoted to studying the acoustic relationships between living organisms and their environments.

Geophony: geo (earth) and phony (sound). Non-biologically, natural sources such as wind, running water, and exploding volcanoes.

Biophony: bio (life) and phony (sound). The “sounds of living organisms” (Krause 2012: 68).

In The Great Animal Orchestra, Krause argues that

The planet itself teems with a vigorous resonance that is as complete and expansive as it is delicately balanced. Every place, with its vast populations of plants and animals, becomes a concert hall, and everywhere a unique orchestra performs an unmatched symphony, with each species’ sound fitting into a specific part of the score. It is a highly evolved, naturally wrought masterpiece. (9-10)

Every organism (flora and fauna) is thus an instrument that oscillates between playing melodies and harmonies. This and the term “symphony” imply that animals and plants exist in a balanced symbiosis where sound plays a pivotal function in its daily operations.

Geophony

In The Lord of the Rings Tolkien repeatedly uses personification to suggest that the Earth of Middle-earth is alive. For example, Water can “murmur” (Tolkien 2007: 121) which means to ‘talk in a hushed or indistinct voice; to make a low continuous sound’ (OED), Air can “whisper” (Tolkien 2007: 136) i.e., to ‘speak softly’ (OED), Caradhras may be able to produce “shrill cries, and wild howls of laughter” and hurl Stones that “whistl[e]” (Tolkien 2007: 289), but most tellingly Legolas listens to and presumably translates the mourning of Stone: “I hear the stones lament” (Tolkien 2007: 284). But Tolkien also presents the Earth as active listeners; when Frodo laughs in the Ephel Dúath (after Minas Morgul but before Shelob’s lair), it “seemed as if all the stones were listening and the tall rocks lean[ed] over them” (Tolkien 2007: 712) and “Tree and stone, blade and leaf were listening” as Aragorn leads the free peoples to the Black Gate after the siege of Minas Tirith (Tolkien 2007: 884).

The Earth of Middle-earth appears very much alive and able to speak and listen (and who knows what else!) on its own terms. Apart from Legolas in Eriador, the voices of the Earth are personified and framed as persons, not as inanimate nor, indeed, empty objects. In Middle-earth rivers have “voices” and mountains can “bre[a]th” (Tolkien 2007: 340-1, 697, 709). One could read this according to Tolkien’s Catholicism where the earth is imbued with the the spirit of the Christian God, medieval organicism, or interest in sciences such as botany (see the fascinating letter 312!) and many scholars and readers have, but here the personified geophony of Middle-earth appears to be a key literary tool for Tolkien to convey a sense that the Earth is, truly, a living organism. When we consider that geo and bio are conceived as separate labels: one meaning ‘earth’ and the other meaning ‘life’, we begin to build a picture that, according to this branch of science that stems from the Enlightenment systems used to categorise the world and frame the earth as inanimate, the Earth is not alive. Tolkien’s writing thus blurs and complicates what should be considered geophony and biophony, asking his readers to reconsider how they view their relationship with the Earth.

Biophony

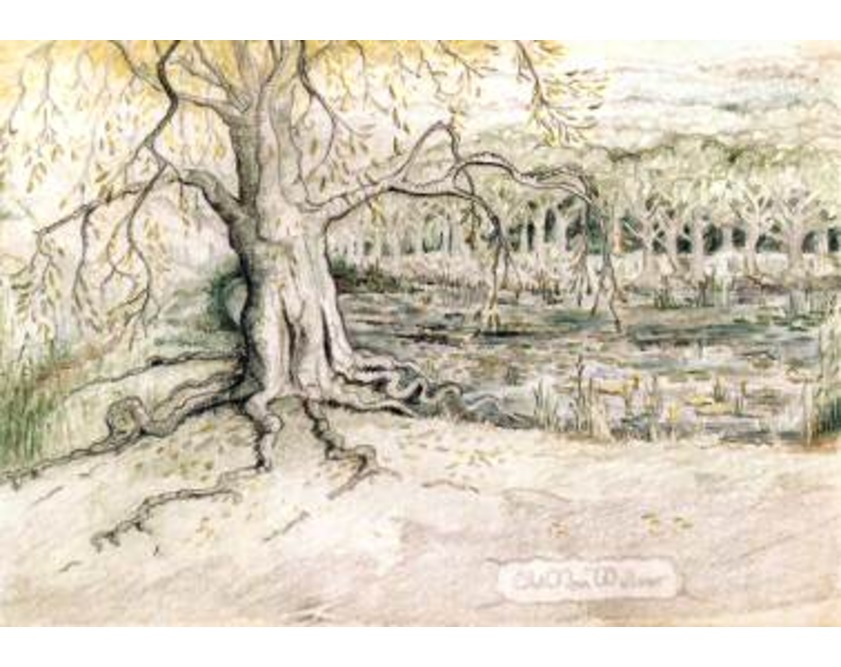

Following on from my previous blog post on Tolkien’s Woods and Forests, it should come as little surprise that I intend to spend this small space wandering back into the Old Forest. When Merry recalls his previous excursion into the Forest he states that “I thought all the trees were whispering to each other, passing news and plots along in an unintelligible language” (Tolkien 2007: 110). The Forest becomes a network of conspirators who appear to communicate, somehow, verbally through the air. Tolkien continues this through to the Withywindle and Old Man Willow who lulls the Hobbits to sleep with “soft fluttering[s] as of a song half whispered” (Tolkien 2007: 117). In response to Frodo’s kick OMW’s Leaves “rustled and whispered, but with a sound now of faint and far-off laughter” and after Sam lights a Fire they “hiss with a sound of pain and anger” (Tolkien 2007: 118). The Trees of the Old Forest are depicted in similar terms to the Wind, Water, and Stone that I addressed above. Like Stone and Caradhras their language is half audible, half perceived by humanoid figures. The text plays with the broader realities beyond the sensory restrictions of Humans, Hobbits, Dwarves, and Elves.

The Forest’s half heard laughter strongly reminds me of the fascinating research into the sonic faculties of animals and plants (Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree 2021 and Ed Yong’s An Immense World 2022 come immediately to mind) and how the world we think we know so well is made up of realities that are altogether beyond our comprehension. Tangentially, William Shakespeare’s oft-quoted “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy” comes to mind! The Old Forest seems to unnerve the Hobbits because of its hostile sentience, but by thinking a little about its biophony, we can start to realise that the Old Forest is utterly alien. And it’s precisely this half-filled space that the Hobbits fill with their own fear.

There’s much more to be said and many case studies to be examined, but here I just wanted to lightly build on some of my previous writing with ideas from music theory. Please do share your own thoughts, reflections, and insights: how else does Tolkien explore the geophony and biophony of his worlds?

Bibliography

Tolkien, J.R.R.. 2007. The Lord of the Rings (London: HarperCollins).

Krause, Bernie. 2012. The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (New York: Back Bay Books).

Leave a comment