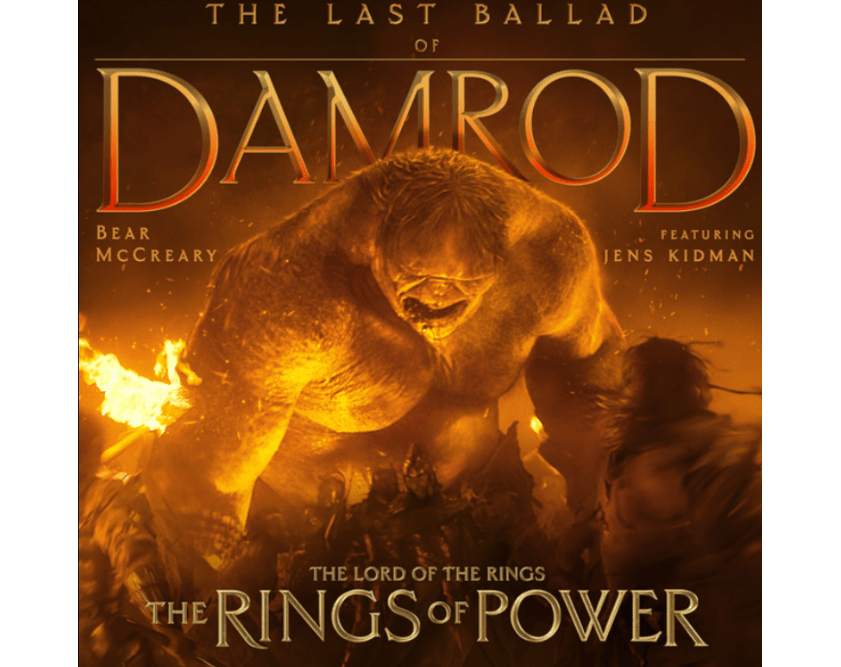

On Wednesday 7th August 2024 Tolkien and metal music fans were treated to a track from the upcoming The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power season 2 score by Bear McCreary. ‘The Last Ballad of Damrod‘ is a metal song produced in tandem with or in the wake of Bear’s metal album project The Singularity (2024). As soon as the track was released, some Tolkien fans had it on repeat while others were uncertain of its place and relevance to Tolkien’s Middle-earth. In this blog post, I’m going to expand on my recent Twitter thread to explore why Bear’s choice to include metal in Middle-earth not only works, but joins an existing musical tradition of employing metal sounds and aesthetics to portray Arda.

Terminology

Throughout this post I will be using some music theory terms. They’re here in case you would like to refer back to them:

- Diegetic – refers to the sounds and music that exist inside Middle-earth: songs such as ‘Far over the misty mountains’, harps, horns etc..

- Non-diegetic – the sounds and music that exist outside Middle-earth: the songs at the end of Peter Jackson’s two Middle-earth trilogies, Donald Swann’s The Road Goes Ever On (1967) song cycle, the songs discussed in the next section.

- Aleatoric – ‘chance’ music: the composer writes a out a set of notes and each performer chooses which note to play where, when, at what speed, how loud etc..

- Dissonant – music that ‘crunches’ together and creates tension.

- Syncopation – when the music does not fall on or follow the clear beat (1 2 3 4) becomes (1 + 2 + + 3 4+)

Tolkien’s Influence on (Metal) Music

As early as the 1960s, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings started to obtain a non-diegetic currency with musicians. Led Zepplin’s ‘Ramble On’, ‘Misty Mountain hop’, and ‘The Battle Of Evermore’ take us into the “darkest depths of Mordor” (in Kemp 2021). Joni Mitchell’s ‘I Think I Understand’ comes from her profound reading of Tolkien and Black Sabbath’s ‘The Wizard’ is a clear nod to Gandalf. There are many others but I want to avoid simply listing examples. If you wish to find out more about the various artists I do/do not include here then see Chris Seeman’s The Tolkien Music List.

Jump to the 1990s with the explosion of various metal sub-genres and suddenly Tolkien’s work becomes a forge in which to fashion new music. Bands took their names directly from the nomenclature of Middle-earth: Amon Amarth, Gorgoroth, Burzum etc., albums were also situated as explorations of Arda: Blind Guardian’s Nightfall in Middle-earth (1998) and all seven of Battlelore’s discography: …Where the Shadows Lie (2002) to The Return of the Shadow (2022). Finally, the sheer number of songs that depict Middle-earth appears endless! It should also be stressed that some of these adapted Tolkien’s works in problematic ways – I’m looking at you Burzum! David Bratman has discredited metal bands as “not interested in Tolkien in any way that serious Tolkien readers would understand as interested in Tolkien; they just think orcs and Nazgûl are cool”, explicitly separating metal music from “serious Tolkien readers” (2010: 153). However, as Brian Egede-Pedersen and Tommy Kuusela showcase, Bratman’s gatekeeping of Tolkien fandom is formulated on a superficial and unfounded reading.

Egede-Pedersen notes that some “black and death metal bands celebrated the darkest parts of Middle-earth by finding names for themselves or their albums in geographical places connected with evil” (2021: 59). Kuusela has observed a not too dissimilar trend, proposing that “Black metal and the use of Antichristian lyrics are naturally inconsistent with Tolkien’s personal world view and his fiction” (2015: 90). However, I would add that their very reaction against Tolkien’s worldview evinces their conscious rejection of a Christian-centric foundation for their music. For these artists the ‘darker’ realms of Arda became a smorgasbord from which to fashion new sonicscapes and explore/question religious-socio-cultural themes and norms – albeit in examples, such as Burzum, this became highly problematic. Bratman’s argument, then, doesn’t hold up: metal adaptations of Tolkien’s material were not simply founded on things that the artists thought were “cool”, rather they appropriated, explored, reframed, and criticised components of Middle-earth through new musical styles, aesthetics, and cultures. Isn’t this ultimately a key facet of the adaptation process? Jackson certainly did this with The Lord of the Rings and let’s not even start a whole critique of The Hobbit!

Now, although Egede-Pederson’s and Kuusela’s statements hold true for these two Nordic-originating sub-genres, other metal groups have sought to explore a much broader set of themes, locations, and characters across the legendarium that do not fall in line with Antichristian or even Christian dogma, destabilising Bratman’s assumption even further. Consider, for example, songs by the power metal band Blind Guardian such as ‘The Lord of the Rings’ (1990), which is a first-person psychological exploration of Frodo’s anxieties and feelings when the Tengwar appears on the One Ring in Bag End, or ‘Nightfall’ (1998) which gives voice to Fëanor’s and his sons mourning over the slaughter of the Noldor. Metal’s engagement with Arda (not just Middle-earth or The Lord of the Rings!) is nuanced, multidimensional, and idiosyncratic to the band and its members.

Tolkien’s works have inspired countless non-diegetic metal bands, albums, and songs: from the genre’s earliest conception to metal today. Tolkien appears across various metal sub-genres and offers a diverse catalogue of opportunities that are not always affiliated with Antichristianity, Christianity, or, in general, religion and faith. Remember, not everything in Tolkien is about religion! Race, sex, gender, morality, ethics, and more are questioned and probed in metal’s adapting of Tolkien.

What makes music ‘metal’?

This is a complex question, and for the sake of this blog post, I will keep it short and clear. There are various tropes, aesthetics, and styles that make up the holistic metal genre some of which I have briefly listed below. I won’t include everything and I bow to 12tone who showcases his excellent knowledge of the genre in his video essay ‘What Makes Heavy Metal Heavy?‘ – quintessential watching!

- Low / Guttural / Screaming: singing in metal can commonly be described as such, although this is not consistent across sub-genres, bands. or artists.

- Heavily distorted guitars: a part of the metal aesthetic but, again, not pervasive. It adds “sonic weight” that creates a “dense, oppressive atmosphere” (Mynett 2017: 14; 12tone 2023).

- Double-kick drumming: the extremely fast, dense playing of the bass drum that can be utilised in short spurts or whole verses/choruses that fashion a “sheer, unrelenting wall of noise (12tone 2023).

- Speed: high, medium, low tempos (speeds) drive the feeling of the music: do I headbang or thrash to this? Virtuoso guitar passages underlie choruses or take up whole ‘solo’ sections of songs. Again, all denote power.

- Power / Intensity / Aggression / Loud: metal has long been associated with these synonyms. These terms have their parallel in literary, artistic, and musical Romanticisms which Amanda Blake Davis and Matthew Sangster have addressed: “we can confidently assert that Romanticism and metal share a preoccupation with power” (2023: 292). But intensity has its natural connection to emotion and expression, a key facet of Romantic art as evinced in William Blake’s ‘The Poison Tree‘ (1794).

I want to linger on this last one here a little as I think it sets the stage neatly for my upcoming discussion of Bear’s song ‘The Last Ballad of Damrod’ (I’m getting to it!). Metal music, as Davis and Sangster propose in accordance with Robert Walser, has its “Romantic-period roots” and although this branches off in various ways, power, intensity, and aggression are useful words when contemplating the creatures that roam Middle-earth, such as hill-trolls (Davis and Sangster 2023: 292). Blake’s ‘The Poison Tree’ argues for the free expression of emotion rather than its repression – which inevitably has volcanic consequences. Emotional expression becomes an avenue of expressing these three ideas and anyone familiar with the ‘unleashed’ sound of metal music will know why I’m stressing this point. Metal frequently flourishes in being an uncontrollable, countercultural phenomenon that challenges and stretches the boundaries of what music, musical culture, and community can be.

A metal tradition in Middle-earth

I grew up with Howard Shore’s scores to The Lord of the Rings. It’s Shore that I have to thank for piquing my early interest in learning about and playing music seriously. But listening to Bear’s new song has made me reflect on the stylistics and aesthetics of Shore’s music and just how metal it really is. I also think Shore neatly proposes an alternative application of metal to the black and death metal bands association with ‘evil’ cultures and geographies.

Let’s start with the ‘Isengard Theme’. It’s instantly recognisable not by the descending brass line, but by the aggressive, dense percussion. An ensemble of players crash, smash, and hit drums, cymbals, piano strings etc. with anything metal (this literally included chainmail!) to create an industrial, powerful sound that is then adopted into the ‘Mordor Theme’ in The Return of the King (2003). Replace the percussion with a heavily distorted guitar emphasising the 1st and 4th beats of the bar (1 2 3 4 5 / 1 2 3 4 5) and you’ve got the start of a real headbanger – I mean . . . who doesn’t headbang to this anyway?!

How about Moria? The moment Gandalf the Grey realises that the Balrog is coming for them, we hear deep, intense male chanting. Indeed, Shore’s ‘Moria’ theme is made up on perfect fifths (known in metal and other genres as power chords) which literally rise before collapsing back into the murky depths of the male voice. You can hear the theme as the Fellowship are jumping over the gap in the stair. Although Shore used the perfect fifths to denote the emptiness of Moria, during the Balrog’s chase he transforms it into the tenacious power chords of the metal genre. Note also the intense chanting during the Company’s escape from Goblin Town in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012).

It is also common for Shore to create senses of chaos and intensity for various elements of Middle-earth. The Watcher in the Water is a perfect example here as Shore writes its music using aleatoric music; strings, woodwinds, and brass swirl, twist, writhe, smash, crash, and blast against one another in a colossal dissonant sound wall that represent the sheer terror of the Watcher emerging from the depths. Aleatoric music is used again and again: Goblin Town, Shelob, Mûmakil, Gundabad, the Dead Marshes. Shore employs metal aesthetics and tropes to convey not just ‘evil’ parts of Middle-earth, but also its denizens and geographies that are ‘unknown’ to the protagonists.

Now, Shore’s music has created what many consider Middle-earth to ‘sound’ like: orchestral, choral, non-electronic. This musical mapping and its various iterations, replications, developments in Shore’s (highly dissonant) later Middle-earth scores and composer’s portrayals of Middle-earth have imprinted this musical expectation on us. So metal at face-value sounds strange because we associate Middle-earth with orchestras and choirs. But the music itself is very in tune with a lot of metal styles and aesthetics, creating diegetic and non-diegetic metal music traditions in and around Middle-earth.

‘The Last Ballad of Damrod’

Okay, so how does all this relate to Bear’s metal song for season two of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power? Well, hopefully if you’ve listened to the song you’ll have been able to pick up on many of the connections. Firstly, Bear collaborated with metal drummer Gene Hoglan and singer Jens Kidman who both featured on his recent metal album The Singularity. Bear describes Damrod as making a “mighty entrance” – immediately note the emphasis on ‘might’ as a synonym for power (Prime Video 2024). In conceiving of Damrod musically, Bear states that “there are elements in heavy metal music that are undeniably appropriate for this troll. We couldn’t help but expand it into a song – like an anthem – for this troll” (ibid.).

Why a troll? Why metal? We’ll have to wait for the show for the details. But look beyond the comedic trolls of Jackson’s The Hobbit (2012-2014) and armoured trolls in The Return of the King (2003), this is clearly a rogue troll of immense strength who, according to the first verse, has “No friend or kin to call his own” and therefore presents an initial threat to all (McCreary 2024). Jackson’s trolls are powerful, yes, but they are still military weapons stripped of individuality and have no musical identity. Damrod therefore represents the raw strength and power of his race. Brass instruments and other orchestral sounds can only go so far (even in Hans Zimmer’s recent scores) so the next step is genre, specifically metal: power, intensity, aggression. As Bear says, the genre is “appropriate” for this troll because of its association with power and strength.

So let’s dig into the song itself. After an opening call where the pitch is bent in a manner that recalls the track ‘Nampat’ and commonly the arrival of Adar, an anxious flurry of strings in a low register signals an uncomfortable and disturbing presence that recalls the string riff from Sauron’s theme – both in uncommon time signatures 7/4 and 5/4. This echoes the aleatoric music that Shore employed and a chaotic propulsion that explodes into two beats at the end of the 5/4 bar (1 2 3 4 5) – a part of Damrod’s theme perhaps that will accompany him in the show? There is a clear theme for Damrod (I’m assuming!) in the brass that is introduced next and continues throughout the song; a slow, syncopated stepping theme that conveys weight, density, and power that wouldn’t sound out of place on distorted guitars. Bear replaces traditional metal band instruments with brass to create a hybrid song: Zimmeresque trombones cleave through the heavy, guttural strings and intense drum set. In amongst the brass is harboured a male chorus percussively stressing their notes on the beat, emphasising the ‘headbanging’ feeling of the song and offering some metric stability against the syncopated brass.

As verse 1 commences, the accompaniment plays what feels like the ‘Dies Irae’ from Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem (1961-1962): syncopated, off-beat, jaunty, cumbersome, weighty, aggressive. The pace of the verse is steady and culminates in the word “roam” where the drums has short. explosive double-kicks that launch the song into the chorus.

The chorus has various components that work to convey Damrod’s power and hostility. The brass return in full, slow force; the chorus sing with Jens to add weight; and on the final two beats of each second bar (1 2 3 4 5 / 1 2 3 4 5) the verb from the line is screamed twice. The verbs are also cacophonic onomatopoeia and convey the sounds of the words: “snap”, “crunch”, “crack” to intensify Damrod’s viciousness and strength. The words are monosyllabic (one syllable) and form clusters of hard-consonants (s, p, c, ch, ck) to replicate the sound of the bones and teeth giving way to Damrod’s hands and jaws. In the chorus’s third and final iteration, strings rise in dissonant thrusts, disturbing the song by racking up the tension and landing on a long-held note in the brass. The opening flurry of strings return while Jens delivers the final, threatening line in a low register that snaps at the end with the ‘t’ of “meat”.

Wrapping Up

I could go deeper but this began with a summary thread and has become its own blog post. Bear’s comments imply that the song will be a credits song (non-diegetic) which will work well. However, given the metal music tradition that already exists in Middle-earth – an orchestral and choral tradition that Bear has already utilised in season 1 – I for one will not be put off by the inclusion of the song over a scene involving Damrod.

Metal music has a long history with Middle-earth and its inclusion in a film/TV adaptation is another addition to this existing tradition. Thank you, Bear, for ‘The Last Ballad of Damrod’.

Bibliography

12tone. 2023. What Makes Heavy Metal Heavy?. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0mo17wLB4Q&pp=ygUTMTJ0b25lcyBtZXRhbCBtdXNpYw%3D%3D

Bratman, David. 2010. ‘Liquid Tolkien: Music, Tolkien, Middle-earth, and More Music’, in Middle-earth Minstrel: Essays on Music in Tolkien, ed. by Bradford Lee Eden (Jefferson: McFarland & Company), pp. 140-170.

Davis, Amanda Blake & Matthew Sangster. 2023. ‘“Load Every Rift”: Power, Opposition, and Community in Romantic Poetry and Heavy Metal’, European Romantic Review, 34 (3), pp. 291-302.

Egede-Pederson, Brian. 2021. ‘”I Head the Sword’s Song, and it Sang to Me”: Adapting Tolkien in the World of Heavy Metal’, in Adapting Tolkien, ed. by Will Sherwood (Edinburgh: Luna Press Publishing), pp. 59-74.

Kemp, Sam. 2021. The 5 greatest musical references to J.R.R. Tolkien. Available at: https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/5-greatest-musical-references-to-j-r-r-tolkien/

Kuusela, Tommy. 2015. ‘“Dark Lord of Gorgoroth” Black Metal and the Works of Tolkien’, in Lembas Extra: Underexplored Aspects of Tolkien and Arda, ed. by Cecile van Zon and Renee Vink (Productie Boekscout.nl Soest), pp. 89-119.

McCreary, Bear. 2024. Bear McCreary – The Last Ballad of Damrod (Feat. Jens Kidman) [LYRIC VIDEO]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjwsf4aopks

Mynett, Mark. 2017. Metal Music Manual: Producing, Engineering, Mixing, and Mastering Contemporary Heavy Metal (New York: Routledge).

Prime Video. 2024. The Lord of The Rings: The Rings of Power | The Ballad of Damrod | Prime Video. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBYUs0u3r2w

Leave a reply to Will Sherwood Cancel reply